“I’m from Mill Basin, in South Brooklyn—I grew up in Brooklyn before it was cool. My dad worked in the Garment District—he was a salesman for women’s scarves and accessories—so I ended up learning a lot about the business. I’d go to showrooms and meetings, and at the end of the day, I’d read the Women’s Wear Daily that he’d bring home. So from the beginning, fashion was a big part of my life. After high school you either went to college or you got married, but the latter wasn’t an option for me. I knew I was going to get an education. I thought about going to Parsons or FIT and doing fashion, but my dad said no. He told me to get a liberal arts education—‘Fashion is in your blood, and you can do that later.’

So I went to the University of Buffalo during the Vietnam War Days—lots of protests and activity there—and I studied communication design, because I didn’t think painting and sculpture would get me a job. Communication design and graphics, all of that felt more marketable. While I was there, I joined Mademoiselle magazine’s College Board Competition. I was one of the 20 winners of their guest editor competition which was a really, really great honor when I graduated…people like Sylvia Plath and Ali MacGraw had won before. 20 of us went to New York together for a month and helped edit Mademoiselle’s September issue and do all sorts of market research. If the contest existed today, it would be a reality TV show.

I graduated in 1969 and went to Europe for the summer with a friend, and when I came back, I had a lot of calls from Mademoiselle to come in for a real, full-time job. I was never really like, ‘I want to be an editor or a writer or something.’ I just knew it was a great place to figure out a lot of things. You got to see different sides of the industry at a magazine. My first job was in the College Competitions department, creating more outreach to students for this guest editor program around the country. Eventually I moved into the Merchandising department, which meant going to every major department store in America and putting on events and shows and bringing the magazine to life. I eventually left, but Condé Nast shut down Mademoiselle later. To me, that was a bad decision—that magazine had infinite wisdom.

Then I got a job as a Fashion Director at a place called Gimbels East, which was a big department store that had an offshoot on the Upper East Side. I loved that job. It was meeting designers and working with the buyers, coming up with the trend boards and fits that we should have, and going to fashion shows. Back then, the fashion shows were very small, and they were all over the place. Very exclusive. I worked there until the corporate changed, and then I opened up a very small PR agency, Fern Mallis Public Relations. I had a lot of friends who were architects and interior designers, and I often said I had 411 on my forehead because people always called me to get everything that they needed. Where do we get invitations printed, or balloons for parties, or spaces for events? One day I was reading Women’s Wear Daily—which I always did—and I saw that the Council of Fashion Designers of America was looking for a new Executive Director and they had been interviewing a ton of people. They had a big AIDS event called 7th on Sale in 1990, which I had gone to, on a dessert ticket. Back then you could buy a ticket for $150 or $200 and come after all of the VIP guests had left. I was very active in AIDS fundraising on the DIFFA board, and that was a big agenda of the CFDA at the time. I sent my resumé and they asked me to come in. I had a really well-rounded profile… I had marketing, PR experience, and a fashion background. I had to meet with a lot of the designers—Calvin [Klein] and Bill Blass, and Carolyne Roehm, who was President of the CFDA at the time. They asked me, ‘Why should we hire you? You haven’t been in fashion in 10 years.’ And I said, ‘I never stopped wearing clothes, I never stopped reading magazines, I never stopped shopping.’ They invited me to their big board meeting next and told me I had gotten the job—that was actually on my birthday.

When I started at the CFDA it was Market Week, when fashion shows would happen. Michael Kors had a show in an empty loft space, with raw concrete walls and ceilings and it was very cramped and very packed. And when they turned the bass music on, chunks of the ceiling started collapsing and came down. Cindy and Linda and Naomi, all the one-name supermodels kept walking. Then plaster landed in the lap of Suzy Menkes from the Tribune and Carrie Donovan from the Times. They wrote scathing articles the next day about how we live for fashion but we don’t want to die for it and how unsafe these places are. I thought, I think that my job description just changed. So when I got into the office, that became a priority to figure out, because there are better ways to do fashion shows. At the time, there were 50 shows, there were 50 locations. Uptown, downtown, everywhere. Nobody really knew where anybody else was showing. All they did was get a time slot that they secured from the fashion calendar, which was a schedule on pink paper that was stapled together. It was not a smooth running fashion week, clearly.

I spent a year and a half looking at empty parking lots, for places where we could do something. We started at the Macklowe Hotel, now the Millenium on 44th Street. Then somehow Stan Herman, who became president of the CFDA and who also sat on the board of Bryant Park, helped us with the Bryant Park negotiations. So we built two tents on the sides of the lawn at Bryant Park. Designers were reluctant to participate initially, but some of them saw the benefit of getting a less expensive space. And we did security, lighting, sound…you just had to bring the clothes.

When we needed to raise money, I spent time calling up everybody. Anna was one of the first people we called, and she said, ‘How much do you need?’ and I said, ‘I don’t know maybe half a million dollars.’ And she said, ‘Let me get back to you.’ She called back and said, ‘We’ll give you $100,000.' And then I called Harper’s Bazaar and I said, ‘Vogue is giving us $100,000.’ And he said, ‘All right, we’ll give you $100,000.’ Then brands got involved—Evian was one of the first sponsors. We had enough money to build the tents at Bryant Park in 1993. Everybody was starting to look for experiential ways to market their brands. We were the first fashion week in the world that had sponsors. And then the marketing strategies changed, from having a box of lipstick samples to really built-out lounges and sophisticated spaces. There were a million nightmares, but it really put America on the map in terms of fashion. The shows would happen in September and February, and everybody was so supportive early on. It was amazing.

Eventually IMG took over Fashion Week, because at a point, [the CFDA was] not so fiscally healthy. I still worked at the tents, because they were my babies. But it started changing—it was a critical time, because IMG took over in 2001, and then 9/11 happened. That morning I was leaving my apartment to go downtown and I knew I was missing the first show, which was at 9 o’clock—it was a maternity show. I was watching CNN because they were doing a special full week backstage report from the tents, and I saw that there was this crash, and I got to the corner of the park and saw the smoke and realized you couldn’t make cell phone calls. Everything was blocked. I got down there and found out how bad everything really was. I went backstage to the folks at Oscar and they were all busy fussing and putting things out, and I said, ‘Stop, turn the music off.’ I really didn’t understand half of what was going on—the seriousness of it all. We were so wrapped up in how to deal with it. I was on the phone trying to work something out and all of the sudden [the person on the other end] started screaming on the phone. I said, ‘What’s the matter?’ He said, ‘Oh my God, the building is coming down. It’s just collapsing.’ You couldn’t even comprehend that. The city transformed. We had a suite at the Bryant Park Hotel and we turned on the TV and sat there and cried at what was going on.

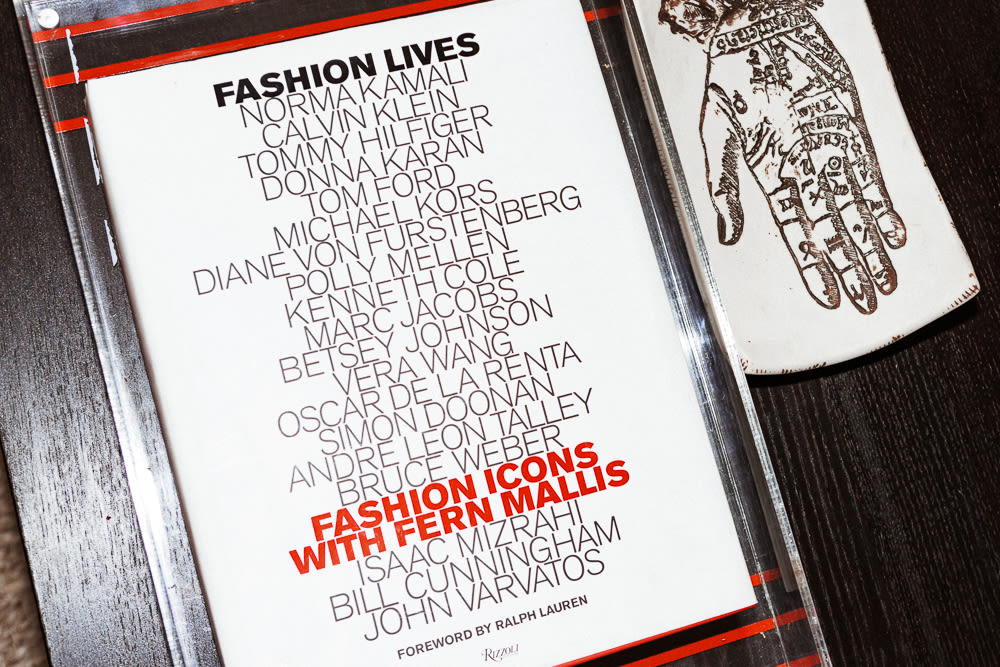

The following season we shrunk the tents and made smaller venues. Nobody felt like they wanted to show for a thousand people anymore cause everybody was still wounded and raw from 9/11. The shows were all much quieter. It took a while to rebuild. I worked with IMG until the end of the Bryant Park shows in 2010, and then I worked on consulting projects. I was also introduced to a woman from the 92nd Street Y, who asked if I’d been interested in hosting a series of interviews with designers. So we did Fashion Icons with Fern Mallis. I got Norma Kamali first and then Calvin and Tommy and the list goes on and on. Now I’m on several boards, and I consult on a lot of regional fashion weeks.

I think now is a very interesting time for shows. I like the discussion that’s going on about the public versus the private shows. Show now, buy now, wear now... I think it’s time to reinvent it all and look at it with a fresh perspective and to do what’s right for the customer. Because at the end of the day, that’s who is buying the stuff. I do agree that social media has changed the discussion. I just walked past the Chanel window the other day, showing clothing I read about months ago, and it seems old to me already. I think if they shifted the model, that would be an exciting thing for America to do and take the lead on. I’m very supportive of that.

Collaboration has been really important in my career, and somewhere along the line, I was told that the the most important thing ever is to just be nice. People really don’t want to work with people they don’t like. There is no reason to. If you want to play the primadonna diva card, go elsewhere. When I was a guest on Project Runway, the four finalists came to my office and asked, ‘What advice would you give us?’ And I said, ‘Be nice.’ And they were like, ‘What?’ And I said, ‘Nobody wants to hire you if you aren’t nice. Nobody wants to do work with you if you’re not nice.’ At the end of the day, you spend more time working with people, and if you don’t like them, it ain’t gonna happen. That’s advice I believe in.”

—as told to ITG

Fern Mallis photographed by Tom Newton at her home in New York on April 28, 2016.