Here’s a trip down memory lane for you: I remember one Christmas during my preteen years when all really I wanted was Jergens “state of the art” Body Shampoo in my stocking. It came in a plastic box with a blue and white sponge, and the sponge featured a little round well that you were supposed to fill with their newfangled liquid soap. Commercials for the product promised a sexy, saxy future, and I was still wallowing in a world of kid showers: sad bars of soap, and no razors allowed. This breakthrough body shampoo “system” was going to be my gateway to smooth legs and revolutionary, womanly cleanliness, I just knew it. It had to be mine.

Well, I did get the Jergens and my prediction came true: months after that yuletide acquisition, I embarked on a lifetime of shaving, and many years of liquid body wash loyalty, minus some (or a lot) of the anticipated glamour. My story is not unique; from the early ‘90s till now, body wash has reigned supreme in the personal hygiene market. It was not until recently, driven partly by thriftiness, partly by half-hearted environmentalism, that I began to revisit the soaps of my youth. I’ve written about my continent-spanning love for Cleopatra, but bar soap’s heritage brands (think Ivory, Dove, Irish Spring) deserve some attention, if not for their effectiveness or ingredients, then at least for their talismanic power.

This series, “The Culture Of Clean,” is about the cultural impact of bar soap, not about its pros and cons. Perhaps, 50 years from now, when we’re getting clean in our sleep via laser technology, allusions to body wash will flood the literary canon, and shower gel will be sung about in ballads, interpreted on gallery walls.

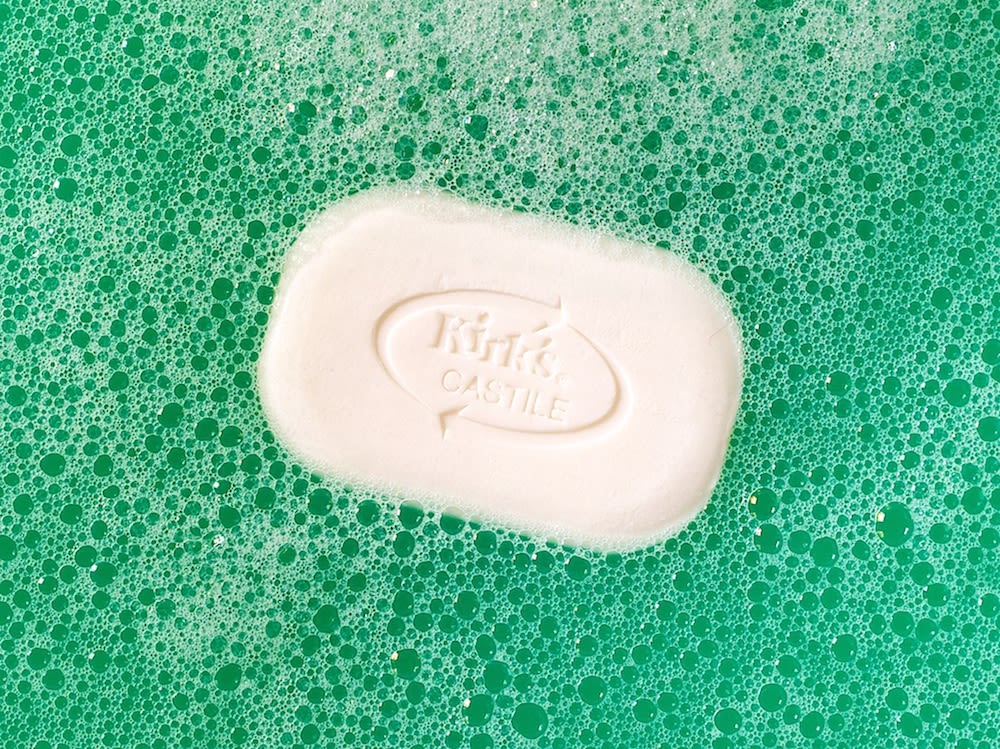

There was an art to soap-making before people made soap into art. Based on early records, the basic formula has remained the same over time: soap comes from combining either plant oil or animal fat with an alkaline base (a.k.a. lye or sodium hydroxide). Scent, shape, and quality varied regionally, and by the Middle Ages, buoyed by Silk Road trade, small-scale manufacturers (or guilds) had formed, their products becoming sought after commodities. Most notable of these early soap-makers were those based in Aleppo (now in modern Syria), and Nablus (in Palestine), and later in Castile, Provence, and Marseilles. White Nabulsi soap is known for being pure and unscented; Savon d’ Alep is made with olive and laurel oils; Savon de Marseille is infused with salt water from the Mediterranean. Castile soap, once preferred by royalty, now refers to any soap made with a plant-based oil .

Painstaking, beautiful processes are employed to maintain the legacies of such soaps—pouring, cutting, stamping, and curing handled with the utmost care. While the tradition of soap-making has thrived in some of these cities (bricks of Savon de Marseille are familiar imports), it barely survives in others. Sadly, war and sanctions have created near-impossible working conditionsfor the artisans of Syria and Palestine.

Mass-produced, commercial bar soap began to appear at the beginning of the 19th century. In England, Pears and Yardley of London became household staples. In America, popular brands like Palmolive and Ivory launched advertising campaigns so relentless (and, in their early days, so racist) they earned the product a permanent place in our cultural lexicon (see: -opera, -box, -derby, wash your mouth out with-, don’t drop the-, et al). And it wasn't just in language that these associations grew. Soap has continued to bubble up in film, literature, art, and design. While the grudge match between bar and liquid rages on in supermarkets and drugstores, the bar is clearly where the art’s at.

—Lauren Maas

Lauren Maas is an Austin-based writer and editor. Photos by Ben Jurgensen.